The year is 2003.

I am [redacted] years old. Before “family”, white tank tops, and impossible bullshit defined the “Fast and Furious” franchise, there was “The Fast and the Furious” – a 2001 film almost exclusively about street racing, “tuner culture”, and the people and their cars that made up an almost imperceptible vertical slice of our world.

We were introduced to nitrous oxide, underglow neon lights, and the Nissan Skyline (at least for folks who hadn’t heard of Jeremy Clarkson’s Motorworld, or watched the Australian Touring Car Championship - Godzilla, anyone?)

It would be remiss of me to suggest that the Fast and the Furious was the first film or television series of its kind. In fact, it was just the latest arrival of a series of media products about street racing and tuner culture. Before Paul Walker’s Supra, there was Initial D’s Toyota AE86, and Wangan Midnight’s Nissan Fairlady Z.

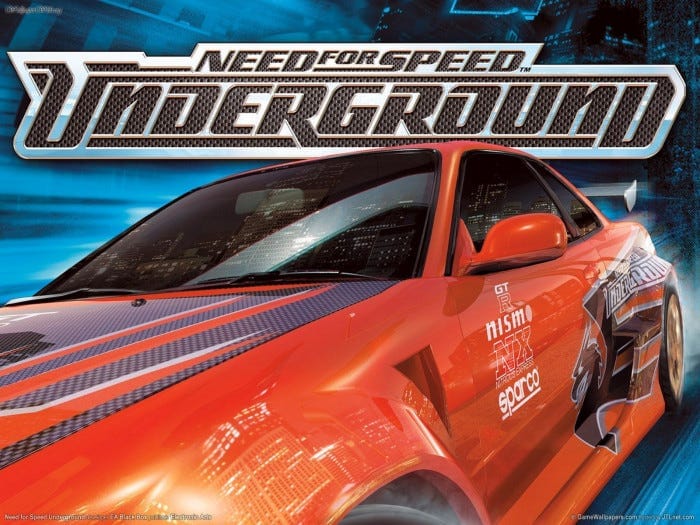

Into this blip on the pop culture radar comes Electronic Arts, well on their way to becoming an unspeakably evil nightmare corporation. With the help of their Black Box development studio, a landmark title in the arcade racing genre was delivered. The culture of street racing, JDM and vaping Subaru owners was immortalized. And it had been driven straight through the crack in the wall made by the Fast and the Furious.

You already know what it is, unless you didn’t read the title.

Need for Speed: Underground.

You (don’t) have to understand, but in the late 90s and early 00s, racing titles were sterile, rigid things. Even something like Gran Turismo, itself a leap forward in the genre (at least for arcade racers, no-one has shit on Papyrus’ Nascar Racing) was about racing on closed tracks with sports cars. The only visual customisation the player had access to were racing liveries, but those also came with upgrades to the car’s performance.

The idea of customising a stock vehicle with cosmetic items like body kits, window tinting and different wheels wasn’t considered as something players wanted in their racing games.

But as Paul Walker and Vin Diesel moved onto the scene, like a perfectly timed switch to wet tires, EA’s development teams pivoted, and dropped a thermonuclear bomb into the racing game market.

And the rest, as they say, is history.

In fact, as a squishy-headed nerd who has a soft spot for history, Need for Speed Underground is a title I find fascinating.

Just like Initial D is a time capsule of Japan’s car culture in the 1990s, the initial trilogy street racing games released by EA (Underground, Underground 2, and Most Wanted) are also a culturally significant time capsule.

They represent a part the 2000s that has not left us in its entirety, but has disappeared from the public consciousness – a similar lifecycle to that experienced by skateboarding in the late 90s – just as Tony Hawk. And whilst the Fast and Furious franchise has long since abandoned the culture which spawned the original film, not to mention the dissolution of Mid Night, the infamous Japanese car club, these games will forever be tiny islands in the stream of time.

I certainly don’t long for these things to return – but it is fascinating to see what was, rather than what is – and to see what was left behind.

Which brings us to the tail end of 2025, and I wanted to play Underground again after watching some clipped livestream footage belonging to Sliphantom, a (retired) Youtuber. I had hobby block, and on a whim, I thought it’d be a cool idea to play the game to completion – something I never did when I wore a younger man’s clothes.

When digesting this review, it is important to understand that Underground is an arcade racer – it features impossible physics, no model damage, and rubber banding. It is, pointedly, not a simulation.

(Incidentally, 2003 was the year Papyrus released Nascar Racing 2003, a PC simulation so good it formed the foundation of iRacing. If you want a simulation, go play NR03)

That isn’t to say you couldn’t use a race wheel and have a blast, but I played through the whole thing on a controller with automatic transmission, and had dangerous levels of fun.

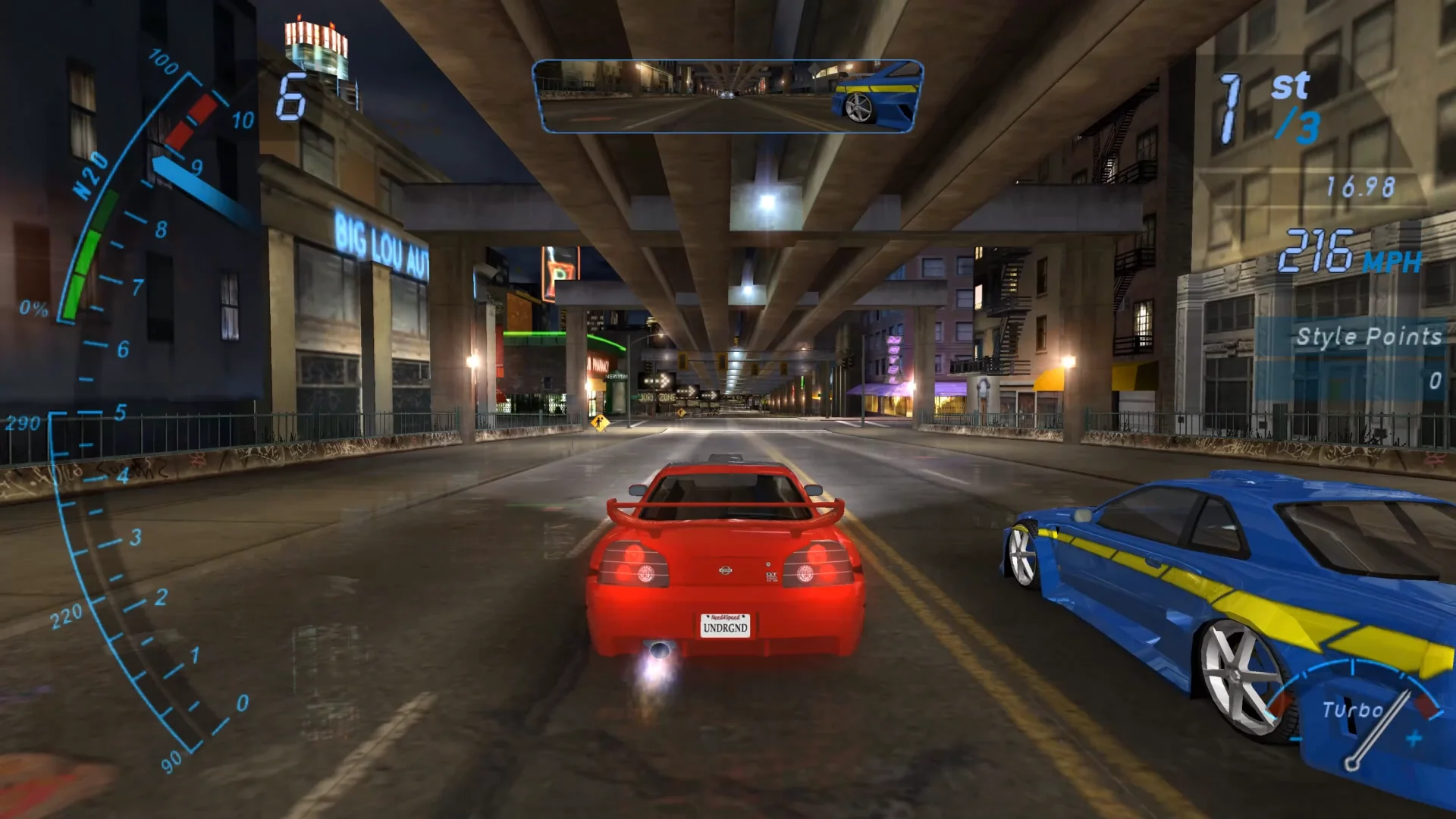

As an arcade racer, NFSU does a lot of things right. The physics of controlling a vehicle feel fluid and responsive, and it’s a lot of fun to slide through corners, before putting your foot down and rocketing along the straights. It doesn’t take too many mechanical upgrades, for you to really feel the speed, tearing through the city streets at warp factor five and effortlessly slicing through traffic. In the game’s late stages, once you really put it all together, you feel a sense of harmony with your garish vehicle, that you have personally ruined with your poor taste, either ironically or unironically.

(And wondering when the cops are going to show up and execute everyone on the side of the road for crimes against common decency.)

And, of course, by the end of the game, your car is so illegal I imagine the highway patrol, if they existed, wouldn’t bother trying to arrest you and would instead skip straight to trying to destroy your vehicle with a guided missile.

Excellent racing physics aside, the real selling point of Underground is the extensive vehicle customisation interface. Playing through the game’s story mode unlocks an extensive menu of visual components for your cars. Body kits, wheel rims, different categories of paint (including the really annoying ones like pearlescent) and something of a signature visual look for both Underground games, underglow neon lights.

As part of the game's customisation interface, the more aftermarket parts you install, the higher your car's star rating, something which can sometimes limit your ability to access races - at least, according to the game's detractors.

The star rating system in Underground does something very important, in that it encourages the player to interact with the visual customisation system. By gating races behind a minimum star rating, a player is forced to continue to interact with the customisation system.

Now, when you start using words like "forced", the spectre of player choice starts to rise from the swamp.

But here's a counterpoint. In Need For Speed: Carbon (and also Most Wanted) the visualisation system is still present but the star rating system isn't. The expectation is that the player will engage with the system, and making their car look "nice" is its own reward. But when players don't have to do something, they won't, and the system becomes optiona. As a result, the system is no longer core to gameplay, and the game feels emptier as a result.

Not just that, but system's mandatory nature being interwoven with Underground's story mode creates an interlinked experience of racing and customisation. Together, the two gameplay loops form a moebius strip of progression which makes the game immersive and addictive. On more than one occasion I had to tear myself away from the computer because “one more race” was proving to be almost irresistible.

You race. Car parts get unlocked. Then installed. Another race to unlock more parts. When you’re racing, you’re thinking about what parts you might unlock next, and when you’re customising your unspeakably hideous imported Japanese two-door sports car, you’re thinking about how awesome it’s going to be to race, then customise, then race again.

Unless it’s a drag race, in which case it’s time to restart 15 times until you get the right string of perfect shifts to win. Something I never noticed as a child, because I loved drag mode when I was little.

Something I adore in Underground as well is when you change your car, all of your visual components get seamlessly migrated across. So if you wanted to see what your upgrades would look like on a different chassis, it's a cinch.

Now when I used the word "story mode" before, I need to honest, reader - that's not really true. It's a framing device. There’s three or four cutscenes in total, not including the opening cinematic, and you're not really introduced to any of the characters, or really asked to care about any of then. There’s also a villain, maybe, who is called supposedly Eddie, who drives a Nissan Skyline, and is very cool and does racing good.

When you go to pick a race from the menu, there’s some extremely mid-2000s introductory dialogue, likely written by an overworked intern who watched too much Music Television, wore wraparound shades, and had a backward baseball cap.

Now with all of that said, you might suspect I've marked Underground down for this, but, surprisingly, no - if anything, I feel the opposite.

Despite being the chosen one who cannot lose a race by virtue of being able to restart every time you plough into the side of a generic white van at 200 kilometres an hour, I like the feather touch of having almost no story elements at all.

With the benefit of hindsight, you can see EA and it's development teams wore criticism about the almost complete absence of a strong narrative in Underground, and started to introduce more in-depth story elements in games like Most Wanted and Carbon.

But they didn't do a good job, and Underground is an example of why, sometimes, you just have to let things breathe.

Because there's very little narrative context, the player has to focus on the things that they can see and feel - the racing physics, the customisation system, and the game's aesthetics.

And let's be clear - Underground is an incredibly aesthetic and immersive experience because of all of those different components working together in harmony.

In his review of Castlevania Josh Strife Hayes, , points out that having a defined style lets a game age gracefully - that is very applicable here.

The dark purples and blacks of the skybox contrast perfectly with the whites, blues and reds of the city lights. You'll see the bright grey tarmac, and orange and yellow safety barriers everywhere - it's incredibly immersive. Then there are the backstreets, industrial areas, cramped markets, highways, and tunnels.

All of which you’ll thunder through with the reckless abandon of a nameless, faceless goon who has purchased $600 worth of plastic tat to stick on the front of their car and cares very little for speed limits, road signs, or other motorists.

And that's without mentioning the soundtrack, an immaculate pairing of pumping rock tunes, high energy techno beats, and who can forget that iconic introductory tune...

At this point, if you’re detecting a thin veneer of bias across the top of this review, you are correct. Particularly as I absolutely hung Golden Sun: The Lost Age out to dry for poor writing.

But Underground is not an RPG, and the writing and doesn’t have to be load-bearing. It needs to frame your existence as part of an underground racing scene, and provide a small amount of context for the races you participate in - and that's it.

Furthermore, what seals the deal for Underground being such a good game, and something that I have kept coming back to, is components that really matter – the racing physics, the car customisation, the track designs – they absolutely shine.

You can easily lose yourself in huge menus cosmetic components, paint colours, wheel rims, and the perfect (highly illegal) neon lighting. And even when you build a “beautiful” car you want to go back and try different parts, and colours, and vinyls.

And then afterwards you get to take your monstrosity and hurtle through Olympic City’s streets at light speed, scaring the fuck out of the law-abiding citizens.

It’s just magic.

You've got to wonder how much money they made on product placement, though...

Catch you next time,

Vulkan

Critical Information Summary

Review Platform: PC

Developer: EA Black Box

Publisher: Electronic Arts

Cost (At Time of Publish): Varies - second hand market only

Did you like this article? Did you hate it? Go over and keep the discussion going on the official Vulkan's Corner facebook page! - whilst you're at it, leave a like!

Rare bonus section! This time, vitriol free!

This will mark the last post for 2025. It's been a year of ups and downs, but being able to project a stream of consciousness out into the world has something I have taken great joy in.

I want to take the opportunity to thank everyone who has stopped by to read (and hopefully enjoy) anything I have posted this year.

And I want wish everyone - friends, enemies, and splenemies, a Merry Christmas, and a Happy New Year - I hope to see you all in 2026.